Various church traditions tend to dam themselves into historical reservoirs, where events of 150, 500, or 2,000 years ago (for example) define them, rather than the wider, longer river. But as the apostle Paul lays out in the first few chapters of his letter to the Romans, what God is doing now only makes sense when we understand what God has always been doing, from the beginning of time. Essentially, Christian history is the story of God’s work in the world since creation.

And before our history became “Christian,” it was Jewish.

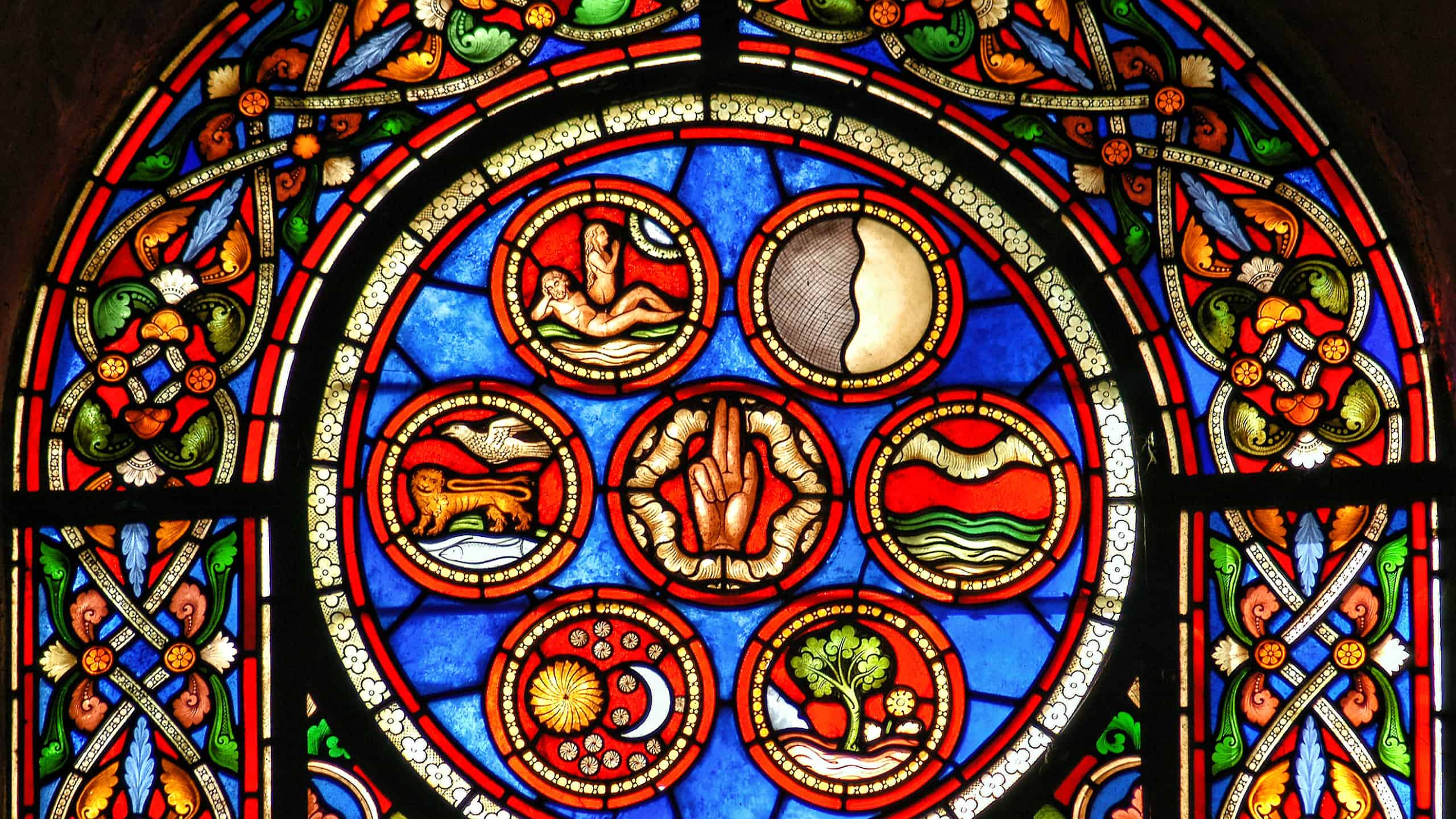

A Unique Cosmology

In contrast to their Near Eastern neighbors, ancient Jews worshiped one supreme God, whom they acknowledged as sole Creator of a good, well-ordered, life-giving world. Rather than celebrating a pagan deity’s hard-won victory over the forces of chaos, their (and now our) creation story reveals the Source of all that exists, for whom the act of creating was not an act of violence but a Word. “Let there be . . .” And there was! (To get a sense of the differences, compare the creation narratives of Genesis 1–2 with Egyptian and Babylonian myths.)

This view of creation has two crucial implications. First, God is the Source not only of all life but also of time, and so humans flourish when we live in rhythm with God’s order. (Observing Sabbath, which reenacts the creation story every seven days, is one key way Jews came to order their lives according to the Creator’s rhythms of work and rest.) And second, because the world of God’s making is good, suffering and injustice are not flaws built into God’s design, but instead are natural outcomes of human rebellion against the Maker’s intended order (see Genesis 3). This means that suffering and injustice can be made right.

Covenant and Salvation

In the Jewish view of unfolding history, God did not abandon deluded rebel humans to an irreversible death spiral of sin. Instead, the Creator initiated a covenant—first with one man, a Mesopotamian migrant herder named Abram, and then with his descendants. (Genesis 12–50 recounts the stories of the Jewish patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.)

Identity as God’s covenant people began to coalesce through events that came to be known as the Exodus, when God raised up Moses to lead Abraham’s descendants out of Egyptian slavery and to institute the Law by which people would govern themselves under God’s rule. (Most widely recognizable are the Ten Commandments, but the full Mosaic Law is far more comprehensive; see the Books of Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.)

Chief among the promises included in the Abrahamic covenant was the “Promised Land,” a nation-state where God’s Law would be the law of the land. In this way, suffering and injustice would give way to the human flourishing the Creator had planned from the beginning. Yet even after the people conquered and then settled the region God had promised, they repeatedly—habitually, even!—failed to abide by the Law. (The Book of Judges is a relentless recitation of these failures and the resulting fallout.) Political and priestly leaders built infrastructure and institutions to implement Law-abiding communal life in Israel (check out 1–2 Samuel, especially), and God inspired prophets to guide people in applying the Law to unique circumstances faced by each generation (for many examples, read 1–2 Kings alongside the prophetic books).

But even with all these advantages, God’s people couldn’t get their act together and live as the Creator intended from the beginning—at least, not for long.

From Catastrophe to Hope

Eventually, rebellion against God’s ordered way of life once again ended in suffering, and the nation-state of Judah was conquered by pagan outsiders. In 587 BCE, the capital city, Jerusalem, was left in ruins while the leading lights of Jewish culture and philosophy were carried away to serve the Babylonian empire. (The Book of Daniel is an insider’s view of this national calamity.)

Over the next several centuries, Jewish identity was shaped by external forces—their homeland overrun by successive empires: Babylon, Persia, Greece, then Rome—and the internal question that always arises from catastrophe: Why? As Jews reflected on their history in an effort to answer that question, they began to assemble stories, songs, sayings, and writings inspired by their enduring, tumultuous relationship with God. (This collection became the Hebrew Bible, which most Christians call the Old Testament.) And as they hoped and prayed toward the future, many began to long for and anticipate a redemptive royal figure known as messiah, which means “anointed one.” Recalling how they had flourished as a people under the rule of King David, they looked forward with hopeful expectation to a new king in the Davidic royal line who would finally usher in the good, well-ordered, life-giving world God had been creating since “in the beginning . . .” (see Genesis 1).

It is into this history—the Jewish story of creation, covenant, and hope—that Jesus of Nazareth, and the Church, were born.