If you check out a map of the Roman Empire at its most expansive (this one, for instance), you can see “Judaea” way over to the right on the eastern frontier. That’s where the Jesus movement was born—and if the New Testament is your only historical reference, you’re likely to come away with the impression that the Christian faith spread west toward the heart of the Empire . . . and eventually, a couple thousand years later, here we are. Certainly that is one part of the story! (Thanks be to God.)

But the Good News of Jesus also surged east and south, first into the regions of modern day Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Libya and then, over the next few centuries, much farther. (Like, China farther. No, really.) Why don’t we hear much today about those non-Western streams of Christianity? The reasons are multifaceted but fall broadly into two categories: theological and historical.

Theological Divergences and the Emergence of Orthodoxy

Theology became a factor first, through the several-hundred-year process of establishing Christian orthodoxy. (Orthodoxy comes from Greek language roots and means “right belief.”) As encounters with the Risen Christ and experiences of the Holy Spirit spread across Arabia, northeast Africa, and the empires of Rome and Parthia, various communities conceptualized Jesus’ relationship to God in different ways. The earliest Christian creed, or confession of faith, was “Jesus is Lord”—but in what way, exactly?

Not everybody agreed on the finer points. Or even (in some cases) on general principles.

The Role of Bishops and the Exclusion of Eastern Churches

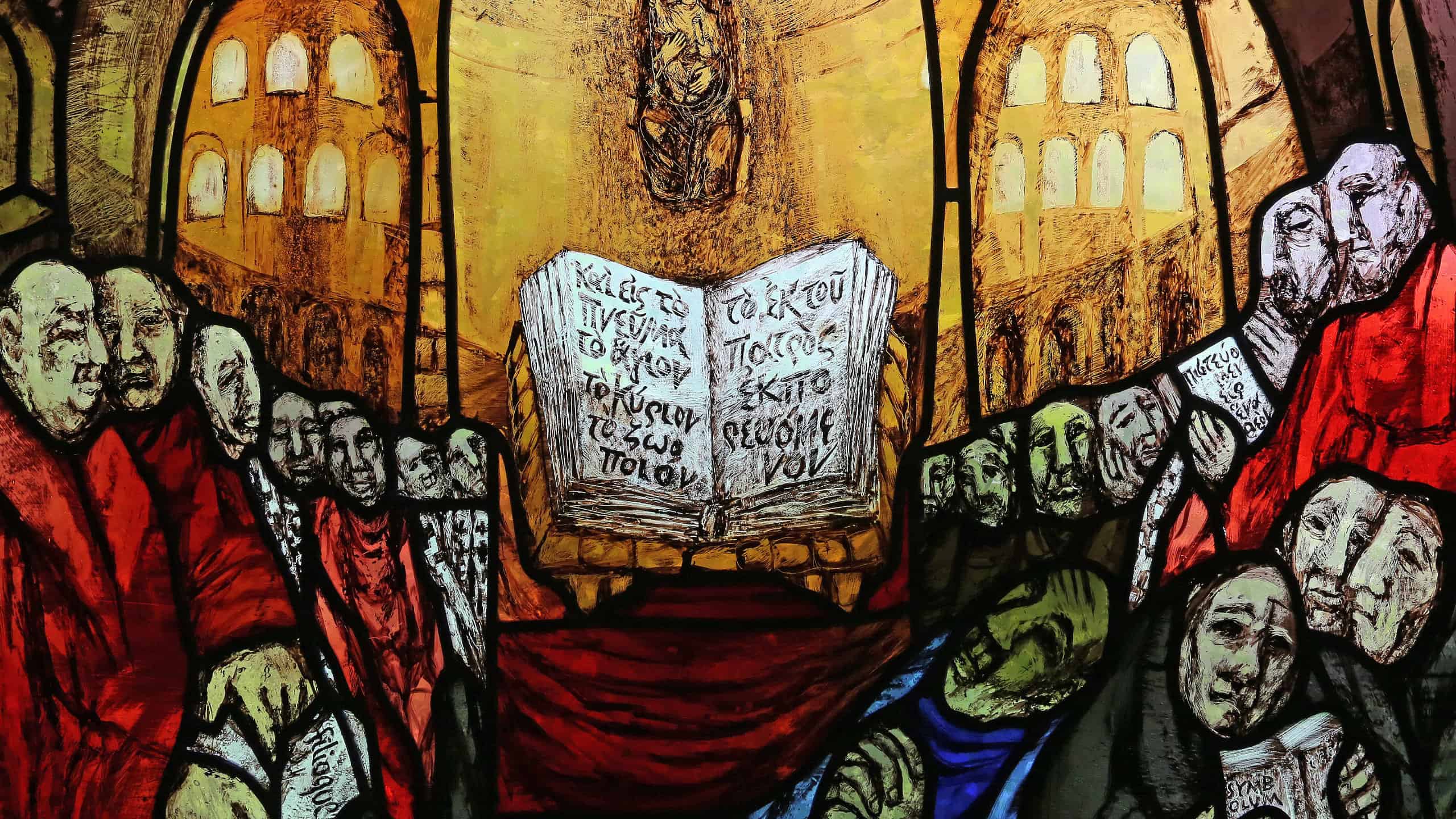

By the early 4th century after Christ’s ascension, bishops (leaders of all the churches in one geographical area, usually based in a city) had begun to use three key means to discern and describe the Lord whom Christians worship: councils, creeds, and the biblical canon. What came to be known as the Seven Ecumenical Councils were called between 325 and 787 and held in various cities in what is today modern Turkey. These locations were roughly equidistant for western, eastern, and southern bishops—like holding a national conference in Minneapolis or Dallas nowadays.

The top (but not only) theological issues on each council’s agenda was the human and/or divine nature(s) of Jesus and how he is related to, different from, or identical with the God of the Hebrew Scriptures and with God the Spirit who lives within those who follow him. The gathered bishops did their best to understand the apostolic witness on these topics, based on early Church baptismal creeds—such as the Apostles’ Creed—and on the Gospels and Epistles that had become sacred scripture in their local city-church communities. (The New Testament canon, the collection of books accepted as genuine scripture, was “closed” or completed by the early 5th century.)

The Continued Practice of Eastern Christianity

City-churches whose bishops didn’t side with the broader consensus on these topics were considered by the majority to be outside the bounds of orthodoxy—and that’s the theological reason we don’t hear much today about the Church in the East. Their bishops did not join one or more consensus views that became orthodox, and were thus considered heretics by the majority and excommunicated (excluded from communion). Heretical, orthodox, or somewhere in between, however, one-third or more of all the earth’s Christians lived in Asia or Africa until at least the 1300s, by historians’ best estimates, practicing their stream of faith by receiving the sacraments, studying the scriptures, and sharing the gospel as the Lord commissioned (see Matthew 28:18–20).

The Impact of Islam and the Shift in Christianity’s Center

Historically speaking, the expansion of Islam during the Middle Ages made a massive impact on the eastern Christian population and on European perceptions about Christianity’s center of gravity. As far as most Latin- and Greek-speaking Church leaders were concerned, pretty much everybody east of Mesopotamia—Iraq, today—was Muslim. By the end of the first millennium after Christ, the Christian “heretics” of the east had been out of sight and mind for two dozen generations, and there is little indication that western bishops were even aware of their existence.

The Latin and Greek Churches: An East–West Schism

The Latin-speaking churches, led by the Bishop of Rome, and the Greek-speaking churches, led by the Bishop of Constantinople, remained in (often uneasy) communion as one holy and apostolic Church until 1054. Many factors—including longstanding cultural differences and secular political maneuvering—led to the formal East–West Schism between the (Latin) Roman Catholic and (Greek) Orthodox Churches that still exists nearly a thousand years later. But two theological disputes lie at the heart of the Great Schism, even to the present day.

The first has to do with how Christians conceptualize the Trinity: Father, Son, and Spirit. Influenced by theologians such as Augustine of Hippo and Boethius, Latin bishops became convinced that God the Spirit proceeds from God the Father and from God the Son. Greek bishops charged this as heresy, because (they argued) it suggests the Trinity is a hierarchy, rather than a fellowship of coequal Persons. Despite Greek concerns, however, Latin bishops added the idea to the central creeds, effectively reshaping settled orthodoxy according to their point of view, without Church-wide consensus. (The disputed wording is known as the “Filioque clause.”)

The second dispute centers on ecclesiology, or how the Church is structured and led (ecclesia is Greek for “assembly”). Based on Jesus’ promise to the apostle Peter recorded in Matthew 16, the Bishop of Rome—whose ecclesiastical authority is inherited from Peter, the first Bishop of Rome, in apostolic succession—claimed primacy over the whole Church. Greek bishops granted that the pope is Peter’s successor, but did not accept that his authority is supreme or infallible. He is, in the Orthodox view, first among equals. The pope’s representatives, visiting the city-church (called a “See”) of Constantinople in 1054, were not pleased with this answer. They responded by issuing a bull (or decree) of excommunication against the Bishop.

The Bishop, in turn, issued a bull of excommunication against the pope’s delegation.

The Break of Communion and the Divergence of Christian Paths

Things went downhill from there.

After a thousand years as one Church, communion was broken. One main channel of Christianity’s river flowed east and the other surged west.