When Martin Luther stood before religious leaders and the Holy Roman Emperor to defend his Ninety-Five Theses and related writings, tradition says he concluded by proclaiming, “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me.” Some recent historians cast doubt on this version of events, but the spirit of Luther’s testimony rings true. As a learned monk, he had applied himself to the study of sacred scripture and uncovered gaps between the Roman Church’s practices and those of the apostolic Church. Luther was not the first or only person to identify such gaps, but he was first to “stand” on his own conscience against the Roman Magisterium.

Luther’s Stance and its Significance

Reliance on one’s own conscience is unremarkable today, but that wasn’t the case 500 years ago. In Christendom, the Church was the arbiter of truth . . . period. And so, when Brother Martin relied on his personal interpretation of scripture and trusted the Spirit to guide him as an individual, he did far more than he intended. Luther became, in essence, the first “modern” Christian.

Let’s take a look at the historical factors that combined to make his unintended innovation our everyday reality.

The Scientific Revolution: Interplay between Science and Faith

Roughly concurrent with the Reformers’ religious experimentation, scholars whose interests lay more with the physical world than with the metaphysical began to develop standards for how to make empirical observations and document their findings. Eventually, those rules became the “scientific method”—which kids today learn alongside spelling words and multiplication tables—and their widespread adoption kicked off the Scientific Revolution.

It would be hard to overstate the extensive cross-pollination of Enlightenment-era Protestantism and science, both of which were fundamentally wisdom-seeking endeavors. In fact, some of modern science’s earliest practitioners viewed their work in specifically vocational terms, feeling as if the Creator had personally called them to observe, hypothesize, and conduct experiments. Devout Anglican Robert Boyle, often credited as the father of modern chemistry, put it like this: “Discovering to others the perfections of God displayed in the creatures is a more acceptable act of religion than the burning of sacrifices or perfumes upon his altars.” But influence went the other way, from science to faith, too—as we’ll see in the life and ministry of John Wesley.

Maritime Exploration and the Drive for Colonization

Also during the same era, long-distance maritime exploration became possible thanks to innovations in both ship construction and sea navigation. Most U.S. schoolchildren know what happened in 1492, but the competing sectarian impulses behind European seafaring are less familiar. The Roman Church underwrote a number of voyages from majority-Catholic nations like Portugal and Spain, partly in hopes of evangelizing and catechizing new Catholics among indigenous peoples before Protestant heretics could corrupt them. (They also wanted to claim untapped sources of gold and silver.) On the other hand, Protestants from England, the Netherlands, and elsewhere tended to be less interested in evangelism than in founding new communities based on their own convictions and interests. (These interests included exploiting local resources for European trade.)

Both Catholics and Protestants assumed that Native peoples would make way and/or assimilate (or be made to), even as they grappled among themselves with theological challenges posed by encounters with an ever-growing number of unchristianized worldviews and ways of life.

The First Great Awakening

European colonization of the Americas went into overdrive through the 17th century, and various faith groups tended to settle together. So, for instance, Calvinist-influenced Puritans founded a colony in what would become Plymouth, Massachusetts, while the English crown (and head of the Church of England) sponsored a colony further south at Jamestown, Virginia. Later, when the evangelical renewal known as the First Great Awakening swept across Britain and its colonies in the 1730s and ‘40s, it thus took on various local flavors according to which stream of Christianity was already being practiced. In New England, for example, revival had a distinctly Puritan zest under the leadership of Jonathan Edwards, whose famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” exemplifies a Calivinist emphasis on God’s sovereignty and human depravity.

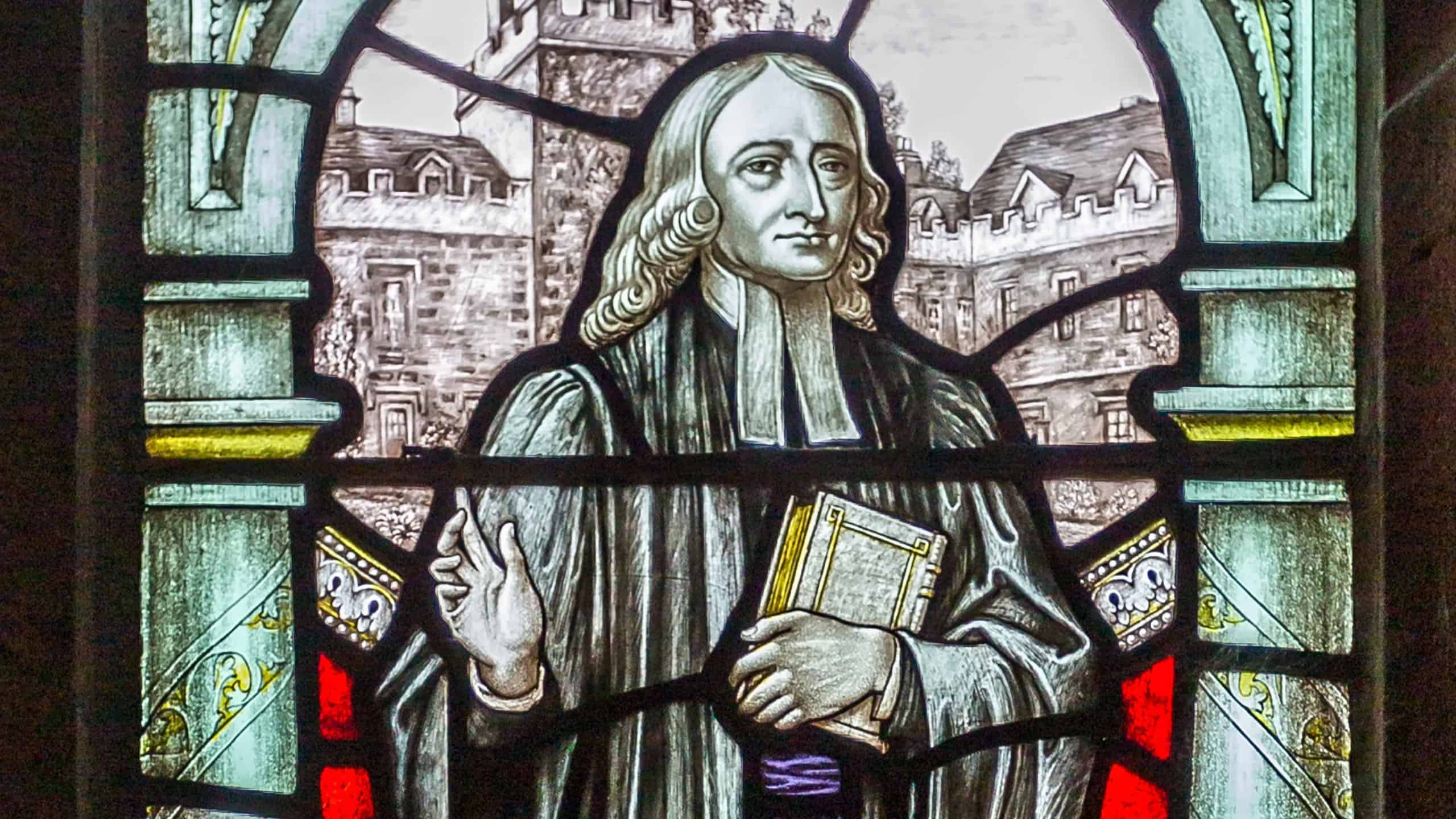

John Wesley and the Birth of Methodism

Back in London, an Anglican priest by the name of John Wesley had spent much of his young adulthood applying systematic methods borrowed from science to his own pursuit of a rich inner life in communion with Christ. Caught by the revival spirit, Wesley had an encounter with the Holy Spirit in May 1738 that came to be known as his “Aldersgate experience,” in which he felt his heart “strangely warmed” in trust and assurance of salvation. So profound was his experience that Wesley embarked on a 50-year preaching ministry that took him far beyond church pulpits to open fields, town squares, and public halls—wherever he could get a hearing for the gospel.

Wesley and his colleagues invited all those who encountered Christ through their ministry to engage with the discipleship methods that had borne such excellent spiritual fruit in their own lives. Their systematized approach to Christian life and community was known even then as Methodism, and its goal then (as today) was nothing less than Christian perfection, or “entire sanctification.” While Calvinists and, to varying degrees, other Reformers rejected the human capacity for Christlike holiness this side of heaven, Wesley and the Methodists were convinced that such a “second work” of the Holy Spirit was not only possible but mandated by the witness of scripture.

Methodism gained a significant following in Britain, but made the impact of a tidal wave in the newly Constituted United States of America—a country founded on the same Enlightenment ideals (reason, individual liberty, human progress) that gave rise to the Wesleyan stream of Christianity. It came ashore just after the American Revolution in the mid-Atlantic region, which had long been home to Anglican colonists. But by the mid-1800s, Methodism had spread to every state and territory, and the Methodist Episcopal Church had become the largest U.S. denomination.